Kamala Harris has been advocating for measures that some describe as attempts to control prices, particularly in response to inflation and rising costs of living. Specifically, she has proposed a federal ban on «price gouging,» which is intended to prevent companies from excessively raising prices on essential goods, such as groceries, during times of crisis.

Capitalists do not like this idea and claim that Harris and the Democrats are Communists. So, why did we spend so much time and money to end the Cold War if we want to control the prices like a Communist country?

During the Cold War, price gouging was a phenomenon that was observed primarily in capitalist countries, particularly during times of crisis, but the context in which it occurred and how it was addressed varied significantly between capitalist and communist states.

In communist countries (Eastern Bloc), price gouging as understood in capitalist terms was less common due to the centrally planned economies. Prices were typically set by the state, not by market forces, and essential goods were often heavily subsidized to ensure affordability for all citizens.

However, this system led to other problems, such as shortages and black markets, where goods could be sold at much higher prices than the official state prices.

In the Soviet Union, for example, shortages of consumer goods often led to long queues and the emergence of black markets where items were sold at inflated prices. While this wasn`t «price gouging» in the traditional capitalist sense (since it was not sanctioned by the market but rather occured outside the official economy) it was a response to the inefficiencies of the planned economy.

In these countries, the official rhetoric condemned profiteering and exploitation, which were seen as capitalist vices. However, the reality of scarcity and black markets meant that some forms of price manipulation and gouging did occur, though they were illegal and contrary to the ideals of the communist system.

In capitalist countries (Western Bloc), price gouging was most notable during economic crisis or emergencies. For example, during the oil crisis of the 1970s, gasoline prices in the United States surged dramatically, leading to accusations of price gouging by oil companies.

Similarly, during natural disasters or periods of scarcity, prices for essential goods could skyrocket. These instances were often met with public outcry and, in some cases, government intervention to cap prices or punish those who were seen as taking advantage of the situation.

The U.S government occasionally imposed price controls to prevent gouging, such as during World War II, and in the 1970s during the Nixon administration, which introduced price freezes and controls to combat inflation and prevent excessive profiteering.

The Cold War era thus illustrates the challenges both systems faced in managing the distribution and pricing of essential goods under different economic models.

But the Cold War is history. So, why are we talking about price gouging now?

It all started in 2018 in France. The Yellow Vest protesters were primarily protesting against the rising cost of living. The movement began in November 2018 as a grassroots protest against a proposed fuel tax hike, which many people felt disproportonately affected low-income and rural citizens who rely on cars for transportation.

The protest quickly grew into a broader movement against economic inequality, high taxes, and the perception that the government was out of touch with ordinary people. They shouted at Trump and his policy; lower taxes, peace, prosperity and freedom.

Legacy Media thought that the protesters were Right-Wing Extremists, but they were ordinary people in all ages. Legacy Media very often turned the picture up-side-down.

The initial trigger for the protests was the announcement of an increase in fuel taxes, which the government justified as part of its environmental policy to reduce carbon emissions. However, many protesters viewed this as an unfair burden on working-class people, particularly those living in rural areas who had few alternatives to driving. In addition, they also increased the cost on toll stations.

Protesters were angry about the difficulty of making ends meet, especially as wages had stagnated while the cost of essentials, including housing and energy, had continued to rise.

So, what is happening in a society when gasolin prices increase? Price on toll stations increase? Energy prices increse? Taxes increase?

The food prices increase.

A study from 2024 showed that oftentimes when allegations of «price gouging» are made, the profit margins of sellers and vendors is substantially lower than critics believe, such as in the case of grocers recently accused of «price gouging» who actually had a 1,2% profit margin after expenses, with Kroger having their highest profits in the previous 15 years occuring in 2018 at 3%.

In March 2024, the Federal Trade Commission accused grocery chains in the U.S. of price gouging. The Commission also sued to block the proposed acquisition of Albertsons by Kroger citing the need for more competition to keep prices down.

In Australia in 2023 and 2024, major supermarket chains Coles and Woolworths received criticism as price gouging, especially in less competitive markets. Coles and Woolworths control 65% of Australia`s grocery market.

A 2022 Working Paper by the International Monetary Fund explores the implementation of windfall profit taxes (higher tax rate on profits), which have gained renewed interest following the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and subsequent surges in energy and food prices.

The paper discusses the potential of such taxes as a tool for efficently taxing economic rents, which are often a result of monopolistic power or unexpected events like pandemics, war, or natural disasters, and contribute to windfall profits. Such profits have raised public and policy concerns about price gouging, where firms are perceived to be profiting excessively from unforseen circumstances.

Price gouging is a pejorative term used to refer to the practice of increasing the prices of goods, services, or commodities to a level much higher than is considered reasonable or fair by some. This commonly applies to price increases of basic necessities after natural disasters.

Usually, this event occurs after a demand or supply shock. The term can also be used to refer to profits obtained by practices inconsistent with a competitive free market, or to windfall profits.

In some jurisdictions of the United States during civil emergencies, price gouging is a specific crime.

Price gouging is considered by some to be exploitative and unethical and by others to be a simple result of supply and demand.

Price gouging is similar to profiteering (unethical) but can be distinguished by being short-term and localized and by being restricted to essentials such as food, clothing, shelter, medicine, and equipment needed to preserve life and property.

In jurisdictions where there is no such crime, the term may still be used to pressure firms to refrain from such behavior. The term is used directly in laws and regulations in the United States and Canada, but legislation exists internationally with similar regulatory purpose under existing competition laws.

It is sometimes used to refer to practices of a coercive monopoly that raises prices above the market rate by deliberately curtailing production. Alternatively, it may refer to suppliers’ benefiting to excess from a short-term change in the demand curve.

Price gouging became highly prevalent in news media in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, when state price gouging regulations went into effect due to the national emergency. The rise in public discourse was associated with increased shortages related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The resulting inflation after the pandemic has also been blamed, at least in part by some on price gouging. During the pandemic, the idea of «Greedflation» or seller’s inflation also moved out of the progressive economics fringe by 2023 to be embraced by some mainstream economists, policymakers and business press.

There is some price gouging-related lawsuits during the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the issuance of emergency price gouging regulations, multiple state attorneys general and federal agencies have investigated potential cases of price gouging impacting consumers and agencies. Since regulatory measures vary in states, there is no uniform interpretation of price gouging violations, and it is left to state courts to decide.

On August 11, 2020, New York Attorney General Letitia James sued Hillandale Farms, one of the largest U.S egg producers, for allegedly price gouging more than four million cartons of eggs by increasing prices by almost five times during the pandemic.

The lawsuit alleges that the price increases were an effort to profit off of higher consumer demand during the pandemic. To Settle the lawsuit, Hillandale Farms agreed to donate 1,2 million eggs to New York food banks.

As of March 2021, Proskauer Rose counted 42 states that have emergency regulations or price-gouging statutes. Price-gouging is often defined in terms of the three criteria listed below:

- Period of emergency: The majority of laws apply only to price shifts during a declared state of emergency or disaster.

- Necessary items: Most laws apply exclusively to items essential to servival, such as food, water, and housing.

- Price ceilings: Laws limit the maximum price that can be charged for given goods.

Washington state does not have a specific statue addressing price gouging, can nevertheless have sought to apply its consumer protection act to argue that high prices during COVID-19 for PPE was an «unfair» or «deceptive» practice.

Statutory prohibitions on price gouging become effective once a state of emergency has been declared. States have legislated different requirements for who must declare a statae of emergency for the law to go into effect.

Some state statues that prohibit price gouging, including those of Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Ohio, prohibit price increases only once the President of the United States or the state`s governor has declared a state of emergency in the impacted region.

The EU does not include «price gouging» explicitly in regulation. Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union is «aimed at preventing undertakings who hold a dominant position in a market from abusing that position.»

As stated, «such abuse may, in particular, consist in: a) directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase of selling prices or other unfair trading conditions….»

In 2016, the EU Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager stated that the EU Commission will «intervene directly to correct excessively high prices» specifically within the gas industry, pharmaceutical industry and in cases of abuse of standard-essential patents.

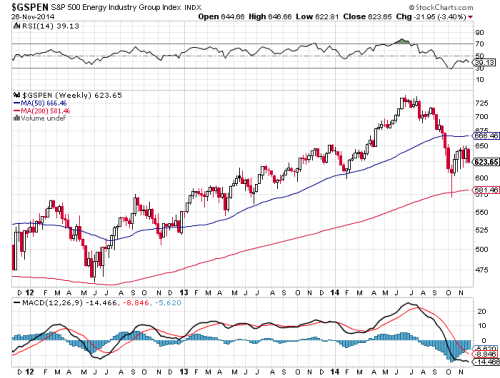

They attack grocery stores with 1,6% profit margin. But what about the oil industry with their profit margin of 30 percent? The Pharmaceutical companies also have up to 30 percent profit margins.

The profit margin in the pharmaceutical industry can vary widely depending on factors such as the type of company (e.g., big pharma, biotech, generic manufacturers), the specific market, and the company’s business model. However, in general, the pharmaceutical industry is known for having relatively high profit margins compared to many other sectors.

For major pharmaceutical companies, profit margins can often be quite high. Net profit margins for large pharmaceutical companies typically range from 15% to 30%. This is due to a combination of high revenue from patented drugs, substantial investment in research and development, and significant pricing power in many markets.

A few large multinational corporations dominate the global oil market, which is characteristic of an oligopoly. This market structure means that while no single company controls the entire market, a small group of powerful companies can influence supply, pricing, and market conditions.

OPEC, made up of major oil-exporting countries, acts like a cartel by coordinating production levels among its members to influence global oil prices. While not a monopoly, OPEC wields significant power over global oil supply and prices by adjusting output based on market conditions.

Allocative efficiency holds that when prices function properly, markets tend to allocate resources to their most valued uses. In turn, those who value the good the most and are able to afford it will pay a higher price than those who do not value the good as much or who are unable to afford it.

According to Friedrich Hayek in «The use of Knowledge in Society» (1945), prices can act to coordinate the separate actions of different people as they seek to satisfy their desires.

Economist Thomas Sowell argue that laws prohibiting price gouging worsens emergencies for both buyers and sellers.

So, let`s hope for a free market unless a crisis occurs.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect those of Shinybull.com. The author has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information provided; however, neither Shinybull.com nor the author can guarantee such accuracy. This article is strictly for informational purposes only. It is not a solicitation to make any exchange in precious metal products, commodities, securities, or other financial instruments. Shinybull.com and the author of this article do not accept culpability for losses and/ or damages arising from the use of this publication.